Hello, blog. It's been a while. It's not you, it's me.

Anyway, of late I was working on the following video - about CSLF Danja, where Mrs H and myself have been living and working for most of this year. Most notable from a production standpoint was that I preplanned more cutaways-per-minute than I ever have before (ending with about 117 separate shots) and yet I still wasn't happy and wish I had gotten more. Such is life.

It's an amazing place and an incredible cause. As Mark says at the end, if you're thinking of supporting somewhere - why not here? Just about every worthy cause you can think of - healthcare, protecting the vulnerable, and quite literally feeding and clothing the poor - goes on here.

It's been a privilege to play the smallest of parts this year.

Find out more about Danja on SIM Niger's new website - the other project that has kept me from much blogging in the past few months!

Thursday, 25 October 2012

Monday, 27 August 2012

your next book #3 - speaking of Jesus

Four weeks ago, I wrote the first draft of a review for the next entry in this 'your next book' series. Even compared to the usual mediocrity, it was terrible. Last week, I tried again, and failed again. So now, I'll must admit defeat.

The book in question is Speaking of Jesus: The Art of Not-Evangelism by Carl Medearis. It is simply one of the best texts on faith I have ever read, and you must buy it, borrow it, whatever. Unfortunately, I struggle to explain why in less than several thousand words, and so will not be reviewing it.

Here's the blurb.

"AUTHOR CARL MEDEARIS is not interested in keeping Christianity alive. Not one bit. Carl believes it has grown into something that is rarely attractive, frequently divisive, and all too often embarrassing. He believes you may feel this way too."

I found myself reading quotes aloud to Mrs H, whether she was listening or not, and then we would debate and discuss them at length. I caught myself exclaiming my agreement and relief out loud. I broke my own rules and was e-mailing people to encourage them to read it.

On one occasion, I was moved to tears by relief and realisation.

Reading this book was as if Medearis lunged inside my soul and successfully articulated that which I could not explain, but had been struggling with and wondering about for years. Frequent stumblers into this interwebulary parish would be able to figure out why after the first few pages. Of that I'm sure.

I am convinced that I will be recommending this book for years to come.

Just don't ask me to explain why (in less than a couple of hours.)

Just don't ask me to explain why (in less than a couple of hours.)

Labels:

books,

christian,

christianity,

evangelical,

evangelism,

faith,

your next book

Monday, 23 July 2012

your next book #2 - longitude

IF YOU DON'T KNOW WHERE YOU ARE, it's very difficult to know where you are going. As in life, so at sea. It's almost alien for us to imagine a world without the ability to navigate, but for most of human history that's exactly how it was.

I had been wanting to read Dava Sobel's Longitude for years, a desire completely constructed on a vague childhood memory of the Bafta-winning TV adaption being rather good. The problem in the spotlight was one of, well, longitude. If you're standing on a ship, one's latitude (that's the imaginary lines running parallel to the equator) can be calculated with simple instruments: the angle of the sun usually covers that one. So you know how far up or down the earth you are quite quickly. Knowing how far around you are is an entirely different matter.

For Longitude is the story of John Harrison, the carpenter who changed the world (no, not that one) by ingeniously engineering the first ever timepieces that were seemingly unaffected by their physical surroundings - all despite, it would seem, the rest of the known world being intent on stopping him.

If, so far, it does not sound like a thrilling prospect, let me reassure you - it undoubtedly is. As no less than Neil Armstrong notes in his introduction, "Those unfamiliar with this unique slice of history will find here a fascinating tale of a remarkable achievement…"

The piece has misguided doubters, skeptics, and downright villains - particularly in the form of the Royal Astronomical Society (they of the Greenwich Meridian) who were set on destroying an opposition to their preferred method of complex star charts and measurements for navigation. Time and time again, Harrison meets opposition. Reading Sobel's incredibly researched accounts, you find yourself wanting to reach into the pages and give characters a good shaking - because in hindsight, that anyone would hinder a man destined to influence all of our lives, everyday, seems sheer selfish lunacy.

But hinder they did. This being historical non-fiction, we know the outcome. But the (rightly filmic) path which Harrison and his marine chronometers travelled, through everything from interference to downright sabotage at the hands of his opponents, makes for a frankly unfortunate series of events. That, in the end, Harrison (by now, an elderly gent) achieves the recognition for his work after decades of opposition only seeks to sweeten the deal whilst simultaneously beggaring belief.

Today, his chronometers rest at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, for so long the headquarters of his opposing inquisition, having been painstakingly restored and finally acknowledged as the solution to the most-sought after intellectual challenge of the pre-enlightenment age.

I had been wanting to read Dava Sobel's Longitude for years, a desire completely constructed on a vague childhood memory of the Bafta-winning TV adaption being rather good. The problem in the spotlight was one of, well, longitude. If you're standing on a ship, one's latitude (that's the imaginary lines running parallel to the equator) can be calculated with simple instruments: the angle of the sun usually covers that one. So you know how far up or down the earth you are quite quickly. Knowing how far around you are is an entirely different matter.

"To learn one's longitude at sea, one needs to know what time it is aboard ship and also the time at the home port or another place of known longitude - at that very same moment. The two clock times enable the navigator to convert the hour difference into a geographical separation."That's not too hard, says you. Just bring someone who can work out the time from the sun, and make sure you set your watch before you leave. But that is precisely the point. It's the 18th century - and the average grandfather clock does not keep time too well on a rocking ship - probably a ship forced to stick to long coastlines and a handful of certain dangerous sea routes to get anywhere.

"As more and more sailing vessels set out to conquer or explore new territories, to wage war, or to ferry gold and commodities between foreign lands, the wealth of nations floated upon the oceans. And still no ship owned a reliable means for establishing her whereabouts. In consequence, untold numbers of sailors died when their destinations suddenly loomed out of the sea and took them by surprise. In a single such incident, on October 22, 1707, at the Scilly Isles four homebound British warships ran aground and nearly two thousand men lost their lives."The whole of Europe was searching for a solution, from the crowned heads of state down. In Britain, Parliament offered the equivalent of over £2,500,000 to the person who could solve this intractable intellectual mindbender. And yet, the solution did not come from the top.

For Longitude is the story of John Harrison, the carpenter who changed the world (no, not that one) by ingeniously engineering the first ever timepieces that were seemingly unaffected by their physical surroundings - all despite, it would seem, the rest of the known world being intent on stopping him.

If, so far, it does not sound like a thrilling prospect, let me reassure you - it undoubtedly is. As no less than Neil Armstrong notes in his introduction, "Those unfamiliar with this unique slice of history will find here a fascinating tale of a remarkable achievement…"

The piece has misguided doubters, skeptics, and downright villains - particularly in the form of the Royal Astronomical Society (they of the Greenwich Meridian) who were set on destroying an opposition to their preferred method of complex star charts and measurements for navigation. Time and time again, Harrison meets opposition. Reading Sobel's incredibly researched accounts, you find yourself wanting to reach into the pages and give characters a good shaking - because in hindsight, that anyone would hinder a man destined to influence all of our lives, everyday, seems sheer selfish lunacy.

But hinder they did. This being historical non-fiction, we know the outcome. But the (rightly filmic) path which Harrison and his marine chronometers travelled, through everything from interference to downright sabotage at the hands of his opponents, makes for a frankly unfortunate series of events. That, in the end, Harrison (by now, an elderly gent) achieves the recognition for his work after decades of opposition only seeks to sweeten the deal whilst simultaneously beggaring belief.

Today, his chronometers rest at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, for so long the headquarters of his opposing inquisition, having been painstakingly restored and finally acknowledged as the solution to the most-sought after intellectual challenge of the pre-enlightenment age.

Friday, 20 July 2012

charitable motivations

EXCUSE ME A MOMENT. I must remove my 'work' hat. There. It's off.

I say this because although we keep a separate, much more lovely blog for all our banter about being in Niger this year, there are of course several (extremely handsome) people who may read both. So it's important you don't get confused, as it's important that I pre-emptively reprimand and separate the comments I am about to make. In fact, if you feel a bit wobbly you should probably just head over there and look at some nice pictures of camels or something.

Fund-raising is the most finely balanced of things for a charity. It's easiest when it's carried by a third party: someone does a fun run, sponsored abseil, makes a donation off their own bat, and so on. They'll use the charity's name so everyone knows what they are doing it for, but it's all on them. For a lot of organisations, this will make up a large chunk of the finances they are able to direct towards helping needy people and causes. We're all familiar with it and are comfortable with how it works.

The internet has been helpful in a lot of ways for spreading the news about these causes. A quick "Hey! I'm doing a sponsored 24-hour biscuit-eating marathon for Save The Badgers! Please donate and help a badger have a happy home this Christmas…" on Facebook, and your JustGiving profile should start filling up nicely as your friends and loved ones chuck a few pennies your way. The web also helps us publicise events, let people know what we're interested in, and generally raise the profile of a cause.

Of course, it's not perfect: a big issue with most fundraising websites is the chunk they take for admin. Generally, I'd rather do cash-in-hand than use them, but even still they let me know how the cause is getting on.

Some charities do it pitch-perfectly. Long time readers may remember this parishes deep, deep affection for charity: water. To my mind, there are few that do it better. Charity: water picked an easily understood cause (digging clean water wells in needy places); you can track every stage of the process from your donation to the physical location it ends up (via a GPS location and a ton of pictures documenting every single well dug); they are completely transparent; and the masterstroke - they worked hard and won corporate friends to cover all the admin costs for the small team of staff. Deservedly an astronomical success, with few gimmicks: donate, people get clean water. Here's the numbers, here the results. Let's go.

Yesterday, one came across the radar which I find much more troublesome. A Christian missions conference in Australia have put up a prize $4000 donation to the charity project which gets the most votes in a Facebook poll on their page. On first glance, it's a great idea - and furthermore, one of the projects is one from our field in Niger. Dutifully, I flagged it up and voted - but immediately on completing the process, I felt like something wasn't quite right.

We make choices all the time about our giving. Should I get a Starbucks, or give some change to the guy on the street outside. Or both? Do I support this charity or this one? How much do I reluctantly drop in the cloth bag on a Sunday morning?

This one is easier though: it costs me nothing to click on the box beside what I know to be an incredibly worthy cause, and help it towards getting a big boost.

But as Mrs H and I discussed what we'd just seen over breakfast, it began to creep up on me - this sense of wrong. It felt like some good old First World Guilt.

To vote, I clicked to this Mission Conference's Facebook Page. I had to like their page first - does this mean the whole exercise, however well-meaning, is mainly for their own publicity? The wealth of updates that appeared on my news feed suggested it might be. Of course a good conference should be publicised, and I doubt that's not the sole motivation for giving. But is it giving - or is it buying airtime?

Then I was presented with the choice of several different causes. It all seemed a bit… "Which of these poor foreign kids will I help today?"

If the conference were so keen to give, why not just nominate a cause rather than giving us a choice? The more I think about it, the more it feels like this is how Simon Cowell would do charity donations. Certainly for the positive PR - but even he picks a single cause every year for his singing contest's charity single.

Perhaps I am overly cynical, or it's a cultural misunderstanding. It is wonderful that a Conference would make a large donation to a suitable cause. I can't emphasise enough the goodness that is no doubt at the root of their intentions. I just struggle to work out which button Jesus would have clicked on.

I increasingly worry that it would be "Close Window".

Labels:

charity,

charity:water,

christianity,

facebook

Wednesday, 27 June 2012

your next book #1 - the white spider

WHY DO PEOPLE seek to conquer? Is it for fame or money? Is it a desire to get one over on nature? Or is there simply an inherent need in all of us to set goals and achieve them?

WHY DO PEOPLE seek to conquer? Is it for fame or money? Is it a desire to get one over on nature? Or is there simply an inherent need in all of us to set goals and achieve them?

For me, this was the central theme of Heinrich Harrer's classic non-fiction text, The White Spider. In 1938, Harrer was one of four men who became the first team to climb the North Face of the Eiger, a 4000-odd metre mountain in the Alps. In his book, Harrer sets out to relate the stories of several attempts made at this alpine challenge, from the first formal undertaking in 1935, and detailing his own team's successful first ascent.

The White Spider came to me under recommendation from the good Mrs H; years ago, her whole family passed the paperback around whilst holidaying in France and the Alps. In retrospect, that sounds the perfect place to have read it; I constantly found myself googling more and more pictures of the Eiger, trying to pick out and visualise every point on the various routes. Harrer succeeds in conjuring up clear visual imagery as he describes the attempts and ascents, but being able to concurrently read and view other documents and pictures of several of the climbers and their endeavours turned the whole thing in to a bit of a study (an experience akin to that of reading Dava Sobel's Longitude - watch this space for that one.)

|

| The North Face of the Eiger. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Something very striking is the specificity of the challenge. The Eiger was first climbed in 1858, 80 years before Harrer got there. Various routes and faces of her and her sister mountains had been climbed and conquered in the interim. But the fearsome North face, which has claimed 64 lives since 1935, was the challenge. What made people risk their lives for success? If mountain has been climbed in four other ways, why does this one matter?

It would be easy to say that the prospective conquerors were seeking fame and fortune. But that is not the world that Harrer portrays. Harrer seeks to show us that the fame-hungry, attention-seeking climbers tended to be the least successful, even wildly dangerous and risk to those around them. The prototype of the successful mountaineer is painted as those who study, painstakingly prepare, and - crucially - know when to call it off.

It's by no means a happy tale; the majority of moments that have stuck with me from the book, four months after reading it, are the most tragic ones. Stories of men dying frozen and alone on the mountain abound. But it is perhaps here that Harrer tells us about those he considers true heroes - the climbers who, often despite official warnings against it, would set out to rescue those who got stuck. In many cases, they knowingly were setting out to recover bodies, rather than men. Some of the most daredevil accounts are those who sacrificed their own attempts, or risked their own lives, to pull their climbing brothers and sisters out of death's jaws. These are the qualities Harrer praises the most:

"If during moments of extreme danger… he thinks first of his rope-mates, if he subordinates personal well-being to the common weal, then he has automatically passed the test… For him, the knowledge that he has done his best is enough. A passion to prove his mettle can never be the mainspring that makes him tick."

In praising the heroes, Harrer is also damning of those he would see as villains. One or two climbers come off particularly badly; those he would see as endangering their fellow mountaineers are not spared his calm wrath. Furthermore, at his most negative Harrer carries out a study of the media frenzy surrounding attempts, and the inevitable tabloid taste for blood.

But overwhelmingly, his positivity is poured out when examining man's motivation for climbing itself.

"What lured him on was, of course, the great adventure, the eternal longing of every truly creative man to push on into unexplored country, to discover something entirely new - if only about himself."

The White Spider made me want to climb stuff. Harrer describes mountaineering as if it is one of the true ends of man; as if, in seeking to conquer peaks, humanity demonstrates the breadth and depth of his goodness and abilities in one fell swoop. Having read The White Spider, you may well find yourself thinking he has a point.

Labels:

books,

heinrich harrer,

review,

the white spider,

your next book

Friday, 22 June 2012

still here

Greetings - particularly to the 500 or so unique visitors in the past 30 days, despite there not being an update published since mid-April. I hope you were able to find the vitriolic diatribe, rambling self-importance, or video of a surprised gerbil for which you were seeking.

Besides posting (just about) weekly on our Niger blog, I'll admit online musings have been at an unusual low of late. The sheer oppression of one's current technical workload (weep, weep) does leave one wishing to flee the machines in one's downtime. (Mrs H will say this is lies, as I'm currently nursing a crippling addiction to the free, Lord of the Rings-aping turn based strategy game Battle For Wesnoth. Download now, geeks. Thank me later.)

Mind you, away from blogging I estimate that I've written and edited somewhere in the region of 40-50 thousands words in the last month or so. (And still no book deal.) Truth be told, this was mostly digesting and condensing the work of others, so I can't claim much credit. Still, add to that coding said words for the new SIM Niger website, and one can feel a headache coming on.

Speaking of coding, a tip of the hat to the creators of HTML Dog, the winner of a close-fought battle to be current reference-guide-of-salvation. I suppose it mostly because the HTML and CSS guides sit nicely alongside each other, and accessibility is pretty good on our dial-up-esque connection. The code I am writing is a mess of trial-and-error learning, but having quick reminders saves heaps of time.

Speaking of coding, a tip of the hat to the creators of HTML Dog, the winner of a close-fought battle to be current reference-guide-of-salvation. I suppose it mostly because the HTML and CSS guides sit nicely alongside each other, and accessibility is pretty good on our dial-up-esque connection. The code I am writing is a mess of trial-and-error learning, but having quick reminders saves heaps of time.

Anyway, back to the premise. Since converting to the cult of Kindle at the start of the year, it seems that I've been able to come back to reading at a rate which had previously dwindled away, probably since university. (It helps to be somewhere with no TV!) So, I'm planning to start publishing some short book reviews here on the blog, to share some of the fiction and non-fiction texts that have sparked the mind - and there are some crackers. Watch this space.

Besides posting (just about) weekly on our Niger blog, I'll admit online musings have been at an unusual low of late. The sheer oppression of one's current technical workload (weep, weep) does leave one wishing to flee the machines in one's downtime. (Mrs H will say this is lies, as I'm currently nursing a crippling addiction to the free, Lord of the Rings-aping turn based strategy game Battle For Wesnoth. Download now, geeks. Thank me later.)

Mind you, away from blogging I estimate that I've written and edited somewhere in the region of 40-50 thousands words in the last month or so. (And still no book deal.) Truth be told, this was mostly digesting and condensing the work of others, so I can't claim much credit. Still, add to that coding said words for the new SIM Niger website, and one can feel a headache coming on.

Speaking of coding, a tip of the hat to the creators of HTML Dog, the winner of a close-fought battle to be current reference-guide-of-salvation. I suppose it mostly because the HTML and CSS guides sit nicely alongside each other, and accessibility is pretty good on our dial-up-esque connection. The code I am writing is a mess of trial-and-error learning, but having quick reminders saves heaps of time.

Speaking of coding, a tip of the hat to the creators of HTML Dog, the winner of a close-fought battle to be current reference-guide-of-salvation. I suppose it mostly because the HTML and CSS guides sit nicely alongside each other, and accessibility is pretty good on our dial-up-esque connection. The code I am writing is a mess of trial-and-error learning, but having quick reminders saves heaps of time.Anyway, back to the premise. Since converting to the cult of Kindle at the start of the year, it seems that I've been able to come back to reading at a rate which had previously dwindled away, probably since university. (It helps to be somewhere with no TV!) So, I'm planning to start publishing some short book reviews here on the blog, to share some of the fiction and non-fiction texts that have sparked the mind - and there are some crackers. Watch this space.

Thursday, 12 April 2012

our friends from across the pond

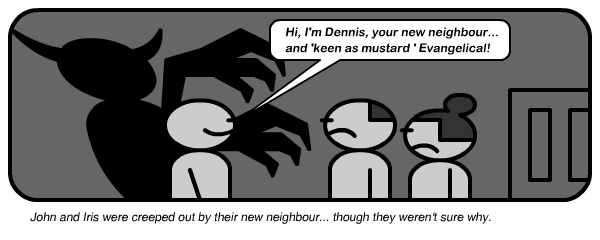

It's a popular debate around my table, the E-word... (no, not Everton - though Paul Rideout's goal in the '95 FA Cup Final remains possibly my earliest memory of getting very upset at a football match, only later matched by my sister mocking my tears ten minutes from the end of the Champion's League final in '99. I digress.)

Within the sphere of faith in the UK, evangelical does not have the same connotations, perhaps, as it does on the other side of the Atlantic. Sadly outside those who understand such distinctions, i.e. the majority of 'normal' people, the difference is meaningless. Six months ago I wrote about the struggle with this label - of being an evangelical - in that whilst I heartily subscribe to the tenets, I also desire to be placed on a different planet from some of those who are best-known and associated with the label.

The world continues to turn. This parish has much respect for Norn Iron's own William Crawley, the BBC's intelligent and thoughtful presenter and producer, and so is cheered to read his latest blog post, in response to finding himself in a room where a change in what American evangelicalism means was obvious to him.

To their credit, I have found the majority of US-born 'evangelicals' I know to be very much of this tribe. Whether we like it or not, the definitions used for American Christianity are those which will often define the rest of us as well in the eyes of a watching world, and so it's encouraging to observe that that same world may be beginning to see things in less black and white terms. The vocal minority will always drown out the well-intentioned majority in the modern mass media, but that doesn't mean we have to put up with their practices - and it seems that slowly but surely, US Christianity may just be waking up to this.

(It's just a pity that it won't necessarily affect the way in which, come November, many pastors will instruct their flock to vote. C'est la vie.)

You can read the full text of Crawley's blog post here.

Within the sphere of faith in the UK, evangelical does not have the same connotations, perhaps, as it does on the other side of the Atlantic. Sadly outside those who understand such distinctions, i.e. the majority of 'normal' people, the difference is meaningless. Six months ago I wrote about the struggle with this label - of being an evangelical - in that whilst I heartily subscribe to the tenets, I also desire to be placed on a different planet from some of those who are best-known and associated with the label.

The world continues to turn. This parish has much respect for Norn Iron's own William Crawley, the BBC's intelligent and thoughtful presenter and producer, and so is cheered to read his latest blog post, in response to finding himself in a room where a change in what American evangelicalism means was obvious to him.

It would be a mistake to assume that American Christians speak with only one voice -- on any issue...

This new generation of Christians have a very different approach to the role of religion in public life...

Instead of a focus on narrow religious or political agendas, they argue that the church should campaign for the common good of society -- standing up for the rights of others, particularly the poor and the marginalised; they are passionate about the need to develop civility in political discourse, where citizens can fundamentally disagree about some basic issues in a spirit of respect while building coalitions on common interest. And, perhaps most significantly, they are standing up against the idea that Christians should seek to build a theocracy.

Instead, this new generation of Christian leader advocates a kind of 'principled pluralism', where difference is protected and respected under the law. That means that you don't outlaw another person's perspective or life-choices simply because they fail to comply with your own theological perspective.

To their credit, I have found the majority of US-born 'evangelicals' I know to be very much of this tribe. Whether we like it or not, the definitions used for American Christianity are those which will often define the rest of us as well in the eyes of a watching world, and so it's encouraging to observe that that same world may be beginning to see things in less black and white terms. The vocal minority will always drown out the well-intentioned majority in the modern mass media, but that doesn't mean we have to put up with their practices - and it seems that slowly but surely, US Christianity may just be waking up to this.

(It's just a pity that it won't necessarily affect the way in which, come November, many pastors will instruct their flock to vote. C'est la vie.)

You can read the full text of Crawley's blog post here.

Labels:

america,

christianity,

evangelical,

william crawley

Thursday, 22 March 2012

misdirection

When I was still an unmarried gentleman of leisure, I developed a certain nightly routine to help unwind. Regardless of how late it was - within reason - I would almost always watch an episode of a DVD boxset before bed. I like to think this allowed for two things: firstly, between 42-60 minutes to expunge the last of the day's stresses and unwind a little; and secondly, to hold on dearly to the idea of making at least three quarters an hour a day which was still very definitely mine.

Since marrying, this has in some ways become a bit of a shared habit. Last year, we ploughed through all but one series of BBC spy-drama Spooks - along with most of the kettle chips and/or crackers and cheese to be found in east Belfast. (Pro Tip: there's nothing quite like grabbing whatever has been reduced daily in the Co-op on the Beersbridge Road.) Shortly before leaving, I decided that enough was enough (at least, that's how I remember it) and that the time had finally come to introduce Ruth to The West Wing, Aaron Sorkin's multi-awarding-winning drama about a fictional US White House. Quite a few people will know me as an evangelist in, and defender of, this show, and I suppose I will remain staunchly so until the day I unwind from this mortal coil.

So six seasons of The West Wing came to Niger, and have been quite literally the only thing we have watched since. We're now in season 6, so I reckon that places us at about one-and-a-half a day, but in reality Saturday mornings account for a lot of that!

But disaster struck this week. Since the DVD drive on my MacBook Pro took a dodgy turn, we had decided to use Ruth's Dell for DVD watching. This was boosted by The Single Useful Idea Dell ever had - Dell MediaDirect, a partitioned part of the hard drive that you can access without turning the main operating system on. That's fancy language for it's really quick and uses a lot less power, ideal for watching DVDs.

But the power cable seemed to have ceased to work. The odd wiggle seemed to cause the blue Power LED to light up, but otherwise, nothing. Panic ensues.

In the UK, this would be an annoyance, but after a bit of fiddling one would probably just log on to Amazon and order a replacement. A little harder here. We are not huge television watchers, but this one little bit of escapism every day or two has already become a moment of comfort to look forward to, a time to relax in the midst of the organised chaos of a mission hospital. We appeared to be now having to adjust to a future where our ways to relax with media - watching and reading - had been exactly halved. Not a tragic hardship by any stretch of the imagination, but a bit of a pain nonetheless.

Now, forgive me, Bartlet-fans. My mind should, of course, be ready to draw down knowledge from the seven seasons of learning that compose The West Wing at an instant. In an earlier time, when things were simpler and the main priority was remembering to lock the door when leaving for class, I would perhaps have instantly recalled that all is not lost in these situations. Let me explain.

In Season Four of The West Wing, in an episode called 'Angel Maintenance', President Bartlet and his staff find themselves stuck, flying around in circles and unable to land, on Air Force One. The problem? An LED indicator, which lights up when the landing gear is fixed into position, has failed to come on. Though a lot of activity ensues, including using fighter jets to check if the gear is in fact in place, the President keeps returning to a salient point made by his pilot at the outset:

In Season Four of The West Wing, in an episode called 'Angel Maintenance', President Bartlet and his staff find themselves stuck, flying around in circles and unable to land, on Air Force One. The problem? An LED indicator, which lights up when the landing gear is fixed into position, has failed to come on. Though a lot of activity ensues, including using fighter jets to check if the gear is in fact in place, the President keeps returning to a salient point made by his pilot at the outset:

After painstakingly dismantling, reassembling and rewiring the unnecessarily complicated 65W power adapter this afternoon with little more than some tweezers and a razor blade, the thought suddenly occurred to me, and so I checked.

The week long worry over the loss of a computer due to a faulty power cable was in vain: it's the flipping light that's faulty.

Since marrying, this has in some ways become a bit of a shared habit. Last year, we ploughed through all but one series of BBC spy-drama Spooks - along with most of the kettle chips and/or crackers and cheese to be found in east Belfast. (Pro Tip: there's nothing quite like grabbing whatever has been reduced daily in the Co-op on the Beersbridge Road.) Shortly before leaving, I decided that enough was enough (at least, that's how I remember it) and that the time had finally come to introduce Ruth to The West Wing, Aaron Sorkin's multi-awarding-winning drama about a fictional US White House. Quite a few people will know me as an evangelist in, and defender of, this show, and I suppose I will remain staunchly so until the day I unwind from this mortal coil.

So six seasons of The West Wing came to Niger, and have been quite literally the only thing we have watched since. We're now in season 6, so I reckon that places us at about one-and-a-half a day, but in reality Saturday mornings account for a lot of that!

But disaster struck this week. Since the DVD drive on my MacBook Pro took a dodgy turn, we had decided to use Ruth's Dell for DVD watching. This was boosted by The Single Useful Idea Dell ever had - Dell MediaDirect, a partitioned part of the hard drive that you can access without turning the main operating system on. That's fancy language for it's really quick and uses a lot less power, ideal for watching DVDs.

But the power cable seemed to have ceased to work. The odd wiggle seemed to cause the blue Power LED to light up, but otherwise, nothing. Panic ensues.

In the UK, this would be an annoyance, but after a bit of fiddling one would probably just log on to Amazon and order a replacement. A little harder here. We are not huge television watchers, but this one little bit of escapism every day or two has already become a moment of comfort to look forward to, a time to relax in the midst of the organised chaos of a mission hospital. We appeared to be now having to adjust to a future where our ways to relax with media - watching and reading - had been exactly halved. Not a tragic hardship by any stretch of the imagination, but a bit of a pain nonetheless.

Now, forgive me, Bartlet-fans. My mind should, of course, be ready to draw down knowledge from the seven seasons of learning that compose The West Wing at an instant. In an earlier time, when things were simpler and the main priority was remembering to lock the door when leaving for class, I would perhaps have instantly recalled that all is not lost in these situations. Let me explain.

In Season Four of The West Wing, in an episode called 'Angel Maintenance', President Bartlet and his staff find themselves stuck, flying around in circles and unable to land, on Air Force One. The problem? An LED indicator, which lights up when the landing gear is fixed into position, has failed to come on. Though a lot of activity ensues, including using fighter jets to check if the gear is in fact in place, the President keeps returning to a salient point made by his pilot at the outset:

In Season Four of The West Wing, in an episode called 'Angel Maintenance', President Bartlet and his staff find themselves stuck, flying around in circles and unable to land, on Air Force One. The problem? An LED indicator, which lights up when the landing gear is fixed into position, has failed to come on. Though a lot of activity ensues, including using fighter jets to check if the gear is in fact in place, the President keeps returning to a salient point made by his pilot at the outset:"The light that indicates that the landing gear is locked didn't go on, which usually indicates that there's something wrong with the light."

After painstakingly dismantling, reassembling and rewiring the unnecessarily complicated 65W power adapter this afternoon with little more than some tweezers and a razor blade, the thought suddenly occurred to me, and so I checked.

The week long worry over the loss of a computer due to a faulty power cable was in vain: it's the flipping light that's faulty.

Monday, 5 March 2012

lawkit volume two: open for business

About this time last year, in a space somewhere between frustration and a lightbulb, this blog featured an article subtitled, 'A Call To Arms'. Initially, this author had intended to continue venting his spleen that he had somehow failed to wake up one morning to a world where he worked in the Bartlet White House.

(And with phrase composition as clumsy as that, I clearly demonstrate just one of the many reasons such a reality has yet to materialise.)

In an effort to placate a personal desire to write something a bit longer than the typical blog post, I had conceived that I could legitimise this effort by roping in others with similar yearnings. A lot of us do not like to sit down and write for writing's sake. And that's fair enough: I don't like motorbike racing.

I put out an open call, particularly to an immediate circle across Facebook and Twitter, for articles, with an open remit for content. Requesting only that they adhere to a rough style guide, and I suppose common decency, potential contributors were given free rein to write on any topic under the sun.

Which is actually more difficult that it might sound. What do you write about when the page is completely blank? When I was in the midst of teacher training, one of the axioms held about English teaching is that it's classroom suicide to give unprepared pupils a blank page and no topic. Not because they'll write something unsuitable: but rather, because the majority will struggle to just choose a subject.

I don't know if that axiom holds true, by the way. And certainly, the responders for the first four issues of The Lawkit, published during 2011 (before time constraints took over in this parish) seemed to sometimes indicate otherwise. In their pages, we covered modern history, football, live music, recipes, political and personal identity, James Bond, and safety when moshing. And these are just the tip of the iceberg.

We had someone describing their mundane desire to get out more.

We had someone else describing the moment they held rubble from Hiroshima in the palm of their hand.

One year on from those initial musings, I am hoping that the time is right to get stuck in to Volume 2. On the editing and publishing side, I hope it was obvious that we improved and tightened the standard of the publication as we went along. We kept everything as open and free-to-use as possible; it was important that The Lawkit could circulate and spread online, unhindered by any questions over a random image that might have come from the BBC website, for example. We also learn a lot about journal and magazine layout as we went along, and hopefully that shows by Number Four. Volume Two should build on this: we have a little brand and identity in the mix now that we like; now it's over to you.

And so, here is the call. Join us in writing something about anything. It could be a page, it could be six. The topic is up to you. If you're stuck, you can read - or reread - the previous issues for inspiration, and maybe to get a feel for the type of thing we go for. But please, think outside the box. Themes always seem to emerge for each issue, so if you're really stuck don't hesitate to ask - but challenge yourself first to see how far you get.

How many times have you heard someone tell a story which seems extraordinary to you, but completely normal to them? Those are one type of story we'd like to hear, for example. But if you would rather write about a personal interest, or respond to something that's in the public arena or currently on your mind, that's also what we're after.

Or maybe you just want to give off about Ryanair. That's ok too. (Though Paul's maybe conclusively covered that one already in Number Two.)

All the previous issues also contain that rough Contributor's Guide I mentioned. We may tweak that in the future, and if that happens before the next issue is published, it will appear here on this humble blog.

What are you waiting for? Fingers at the ready...

(And with phrase composition as clumsy as that, I clearly demonstrate just one of the many reasons such a reality has yet to materialise.)

In an effort to placate a personal desire to write something a bit longer than the typical blog post, I had conceived that I could legitimise this effort by roping in others with similar yearnings. A lot of us do not like to sit down and write for writing's sake. And that's fair enough: I don't like motorbike racing.

I put out an open call, particularly to an immediate circle across Facebook and Twitter, for articles, with an open remit for content. Requesting only that they adhere to a rough style guide, and I suppose common decency, potential contributors were given free rein to write on any topic under the sun.

Which is actually more difficult that it might sound. What do you write about when the page is completely blank? When I was in the midst of teacher training, one of the axioms held about English teaching is that it's classroom suicide to give unprepared pupils a blank page and no topic. Not because they'll write something unsuitable: but rather, because the majority will struggle to just choose a subject.

I don't know if that axiom holds true, by the way. And certainly, the responders for the first four issues of The Lawkit, published during 2011 (before time constraints took over in this parish) seemed to sometimes indicate otherwise. In their pages, we covered modern history, football, live music, recipes, political and personal identity, James Bond, and safety when moshing. And these are just the tip of the iceberg.

We had someone describing their mundane desire to get out more.

We had someone else describing the moment they held rubble from Hiroshima in the palm of their hand.

One year on from those initial musings, I am hoping that the time is right to get stuck in to Volume 2. On the editing and publishing side, I hope it was obvious that we improved and tightened the standard of the publication as we went along. We kept everything as open and free-to-use as possible; it was important that The Lawkit could circulate and spread online, unhindered by any questions over a random image that might have come from the BBC website, for example. We also learn a lot about journal and magazine layout as we went along, and hopefully that shows by Number Four. Volume Two should build on this: we have a little brand and identity in the mix now that we like; now it's over to you.

And so, here is the call. Join us in writing something about anything. It could be a page, it could be six. The topic is up to you. If you're stuck, you can read - or reread - the previous issues for inspiration, and maybe to get a feel for the type of thing we go for. But please, think outside the box. Themes always seem to emerge for each issue, so if you're really stuck don't hesitate to ask - but challenge yourself first to see how far you get.

How many times have you heard someone tell a story which seems extraordinary to you, but completely normal to them? Those are one type of story we'd like to hear, for example. But if you would rather write about a personal interest, or respond to something that's in the public arena or currently on your mind, that's also what we're after.

Or maybe you just want to give off about Ryanair. That's ok too. (Though Paul's maybe conclusively covered that one already in Number Two.)

All the previous issues also contain that rough Contributor's Guide I mentioned. We may tweak that in the future, and if that happens before the next issue is published, it will appear here on this humble blog.

What are you waiting for? Fingers at the ready...

Friday, 2 March 2012

thorny topics

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson

There's a blog post which will land here at the start of next week which will return us to the conversation about the desire to write. I have to admit, that's a desire which is, in a way, being heavily slaked at the moment.

Like all folk who serve with the backing of others, we undertook to frequently report back throughout our year living and working in Niger. In addition, what with my role as communications coordinator, coupled with, you know, always banging on about writing stuff, it seemed like a good time to show up and deliver for once. So, we pledged to blog at least weekly, and also write something longer and prayer-orientated for our signed-up supporters on a monthly basis.

Now there's the usual pitfalls for sure. What seemed remarkable a month ago already has lost the air of noteworthiness; an element of the nothing-really-happened-this-week sits heavy on fatigued imaginations from time to time.

However, all of this week I have been attempting, and failing, to cross a pothole of a different breed. The things you want to write about, but can't. Or the things you would like to describe, but fail to.

I'll explain what I mean, but firstly let me flag that I'm not referring here to some massive conspiracy to cover up truth! I'll start from another angle.

As aliens in this environment, we see and come across things that we have literally never seen before. We do things that we have never done before at a frequency significantly higher than we would experience in our natural habitat. Like poking a chameleon, for example. Today I poked a chameleon, and picked a little at the dead skin on his back. (More on that over on DesertHueys later, I would imagine!) One does not see a lot of chameleons where I grew up in Mid Ulster.

There's a political metaphor there if you happen to be feeling a bit waggish, but we'll move on.

There's also shocking things, naturally. In one of the least developed countries in the world (I've lost track, is Niger back at second or third worst?) there's no shortage of upsetting sights and sounds. And describing them is the problem. In fact, it's a problem which has held up my writing of our e-mail update for this month all week.

In this case, it's traditional healers. That's what I want to write about. Traditional - i.e. local - medicine is encountered daily by the doctors working here. I want to write a respectful, understanding piece for our friends and family back home, describing some experiences around that. I perceive it to be a very sensitive topic. I could write in stark terms and short brushstrokes - there's a lot to tell.

But across all those cultural divides, how do you write about these things and complete avoid a blindly critical tone? How do you avoid saying something is plainly right or wrong?

Maybe you don't. Maybe that's the problem, and maybe that's what I'm afraid to say. But the mission we work for is bigger, older and more important than us. And if burying vitriol until a reasonable discourse can be produced instead is the key to preserving such things, that's the way it has to be.

These thorny topics produce difficulties for aid NGOs all the time. Our communications manuals are full of them. It's not political correctness per say; but the problem is that so much of our work is based around mutual respect, goodwill, and relational ministry. You can't do that if you're impersonally criticising left, right and centre. You don't bring cake to the dinner party, and then slag off the undersized main meal. The difficulty for us is to find a way to lovingly - and usually, painstakingly slowly - build a relationship to a point where friends can be honest with each other.

All to say, I probably owe an apology, available to anyone who may have strayed from DesertHueys over to here, as to why you didn't receive an e-mail update in February. One is coming very soon. The luxury we have is that our deadlines are flexible, and I'm working this one just a little longer.

Thursday, 23 February 2012

the god with sore legs

I've been God-bothering for over a decade, I suppose. I can also be a ferocious reader when time permits. However, these two things have not always lined up: usually preferring Pratchett to Piper, I have actually only finished a handful of the western world's deluge of such publications.

I figure Christian literature is similar to Christian music - there's some genuinely wonderful pieces of work, but there's also a huge mountain of filler. (Particularly the ones with the perfectly-coiffured author beaming their prosperity gospel smile from just about their name in massive gold text... sorry, I'll stop. Even evangelists need private jets.) So I've started many, but have only made it to the epilogue of a few - Mike Yaconelli's Dangerous Wonder; Rob Bell's first two - Velvet Elvis and Sex God; Brennan Manning's The Ragamuffin Gospel; David Crowder and Mike Hogan's Everybody Wants To Go To Heaven (But Nobody Wants To Die); and a Max Lucado devotional, of which the name escapes me. I honestly can't think of any more at this point, though I'm sure there must be one or two.

Naturally, all the above therefore come highly recommended - they managed to hold my attention for 250-400 pages, so the would have to be. But in the past week I've added another to the list: The God With Sore Legs, by Adrian McCartney.

Naturally, all the above therefore come highly recommended - they managed to hold my attention for 250-400 pages, so the would have to be. But in the past week I've added another to the list: The God With Sore Legs, by Adrian McCartney.

Now, I declare an interest. It's hard NOT to want to finish a book where you probably know the majority of people and places named. I reckon Adrian is notorious enough around Belfast to shift a few copies to those who are just curious. But I'm very pleased to say that after ten pages, I was completely hooked. Adrian has written a book which is inspiring, funny, soul-searching and devastatingly honest about faith. I laughed out loud and was moved to put it down and ponder hard within pages of each other.

However, it is far too nice about Ryan, from my (particularly footballing) experience. But we'll touch on that again before the end.

The book's structure is promising, and there are roughly three strands. The pledge, around three cycling trips around parts of Ireland - the Ards peninsula, through south Down, and from Newry to Wicklow - provides a travelogue that, whilst not exactly Bill Bryson, is both thorough and humorous. The turn involves stories and insights from past experiences and lessons learnt from Adrian's own ministry. The prestige, and what binds the story, is an exposition of John's gospel and the man, Jesus, that is met and observed there. It's a strong mix - as the author jumps with ease between these strands and finds many common thoughts and crossover points, it's great fun to gently pedal along behind him.

Reading the Kindle edition, I've pulled up 14 different notes that I highlighted as I read. Granted it's really 12: one is reference to a yellow house, which I highlighted because I suspect, by coincidence, I know the residents, and the other reads, 'Ryan has the most complex mind I have ever HAD to listen to' (emphasis added.) But still, for this reader, that's a lot of note taking.

The God With Sore Legs is not a complex theological works, though it does have it's profound moments. When it handles John's writings, it is not a thorough expansion of the text. What does do, however, is provide a readable, informal and crucially outreaching look at Jesus. No bells, no whistles, just the man and his actions - and consequently, what they mean for us. I was taken with his humanness as he grew from Jesus the boy to Jesus the man, for example:

I feel this is one of the real strength's of Adrian's effort here: making Jesus the man seem real. Not a character; not only a God; but human. Really, really human, with temptation, with emotions, with growth and learning. Just sit for a moment and consider: even Jesus had sore legs at the end of a day's walk.

Knowing Adrian's ministry of the past few years, it's no surprise that he puts so much effort in the book into demystifying the Son of God - that the grace of Jesus is not behind a veil, accessible only through a building with a steeple on a weekly basis, but rather living and breathing in every part of every place. Even Dundalk. Applying that further on to it's ramifications for community, unsurprisingly, is also therefore a topic of much discussion.

This book is packed with simple but undervoiced truths, and it greatly pleases me to heartily recommend it to this small corner of the web.

Even if it is too soft on Ryan.

'The God With Sore Legs' is available on Amazon.co.uk (for Kindle) or from Amazon.com (print and eBook).

I figure Christian literature is similar to Christian music - there's some genuinely wonderful pieces of work, but there's also a huge mountain of filler. (Particularly the ones with the perfectly-coiffured author beaming their prosperity gospel smile from just about their name in massive gold text... sorry, I'll stop. Even evangelists need private jets.) So I've started many, but have only made it to the epilogue of a few - Mike Yaconelli's Dangerous Wonder; Rob Bell's first two - Velvet Elvis and Sex God; Brennan Manning's The Ragamuffin Gospel; David Crowder and Mike Hogan's Everybody Wants To Go To Heaven (But Nobody Wants To Die); and a Max Lucado devotional, of which the name escapes me. I honestly can't think of any more at this point, though I'm sure there must be one or two.

Naturally, all the above therefore come highly recommended - they managed to hold my attention for 250-400 pages, so the would have to be. But in the past week I've added another to the list: The God With Sore Legs, by Adrian McCartney.

Naturally, all the above therefore come highly recommended - they managed to hold my attention for 250-400 pages, so the would have to be. But in the past week I've added another to the list: The God With Sore Legs, by Adrian McCartney.Now, I declare an interest. It's hard NOT to want to finish a book where you probably know the majority of people and places named. I reckon Adrian is notorious enough around Belfast to shift a few copies to those who are just curious. But I'm very pleased to say that after ten pages, I was completely hooked. Adrian has written a book which is inspiring, funny, soul-searching and devastatingly honest about faith. I laughed out loud and was moved to put it down and ponder hard within pages of each other.

However, it is far too nice about Ryan, from my (particularly footballing) experience. But we'll touch on that again before the end.

The book's structure is promising, and there are roughly three strands. The pledge, around three cycling trips around parts of Ireland - the Ards peninsula, through south Down, and from Newry to Wicklow - provides a travelogue that, whilst not exactly Bill Bryson, is both thorough and humorous. The turn involves stories and insights from past experiences and lessons learnt from Adrian's own ministry. The prestige, and what binds the story, is an exposition of John's gospel and the man, Jesus, that is met and observed there. It's a strong mix - as the author jumps with ease between these strands and finds many common thoughts and crossover points, it's great fun to gently pedal along behind him.

Reading the Kindle edition, I've pulled up 14 different notes that I highlighted as I read. Granted it's really 12: one is reference to a yellow house, which I highlighted because I suspect, by coincidence, I know the residents, and the other reads, 'Ryan has the most complex mind I have ever HAD to listen to' (emphasis added.) But still, for this reader, that's a lot of note taking.

The God With Sore Legs is not a complex theological works, though it does have it's profound moments. When it handles John's writings, it is not a thorough expansion of the text. What does do, however, is provide a readable, informal and crucially outreaching look at Jesus. No bells, no whistles, just the man and his actions - and consequently, what they mean for us. I was taken with his humanness as he grew from Jesus the boy to Jesus the man, for example:

Did Jesus really have to grow in wisdom? Did Jesus really have to grow in favour with God? Did he really have to grow in favour with the people around him? Yes, yes, yes. He had to grow just like you or me. He did not need to win God over but he did have to grow in his understanding of him and in his understanding of humanity and of the world in which God and humanity might meet.

To become like s he voluntarily emptied himself so that he could be one of us. This is the greatest mystery of the whole thing. How can God become one of us? Only by emptying himself.

I feel this is one of the real strength's of Adrian's effort here: making Jesus the man seem real. Not a character; not only a God; but human. Really, really human, with temptation, with emotions, with growth and learning. Just sit for a moment and consider: even Jesus had sore legs at the end of a day's walk.

Knowing Adrian's ministry of the past few years, it's no surprise that he puts so much effort in the book into demystifying the Son of God - that the grace of Jesus is not behind a veil, accessible only through a building with a steeple on a weekly basis, but rather living and breathing in every part of every place. Even Dundalk. Applying that further on to it's ramifications for community, unsurprisingly, is also therefore a topic of much discussion.

I think Jesus wants to make friends there and not just try t get them out of there. That is why it has never bothered me that they don;'t come to church.

Someone said that the true test of the character of any family or community is its attitude to those who are outside of it. God's wee family in heaven has always looked outside of itself. Firstly when they created us. Secondly when they worked out the plan to win us back. Thirdly when they sent one of themselves to show us how to live and to die for us. Fourthly when they sent another one of the three to live among us and inside of us. And then constantly when they listen to us whining and complaining and asking for lottery numbers and blessings and riches and good barbecue weather and attractive looks and fame.

This book is packed with simple but undervoiced truths, and it greatly pleases me to heartily recommend it to this small corner of the web.

Even if it is too soft on Ryan.

'The God With Sore Legs' is available on Amazon.co.uk (for Kindle) or from Amazon.com (print and eBook).

Labels:

adrian mccartney,

amazon,

books,

kindle,

review,

the god with sore legs

Tuesday, 7 February 2012

how to write

Readers of our Niger blog might be surprised to know that I feel a certain amount of writer's block at the moment. (On closer inspection, you might realise why I've suddenly converted to photo blogging!) It is, however, with some sense of irony that I've realised in the past couple of days that despite now being in a post for the year where writing is a key tenet, my recent attempts are feeling less than satisfying.

I would show some examples to illustrate this, but then you might lose the impression that I'm a literary genius, and we can't have that.

In my mild angst (you can only be so angst-y when the daily temperature is thirty degrees warmer than your body is used to) I have sought relief at a oft-visited source - the delightful blog Letters of Note, which daily publishes a piece of correspondance that is... well, noteworthy. A recent highlight which I tweeted a few days back was this wondrous reply from the American author E.B. White - he of Charlotte's Web and The Elements of Style fame - on behalf of his dog to the ASPCA. Joyful stuff.

Anyway, I discovered yesterday that the curator, Shaun Usher, recently also opened Lists of Note, which is exactly what it sounds like. And recently, there have been two posts on the subject of writing - both of which I'm quoting below, with no credit taken at all.

First was the great Henry Miller's 11 Commandments:

This morning, whilst relocating the Miller post, I noticed that today's post is also about writing. Manhattan advertising overlord David Ogilvy sent a memo in 1982 to his employees:

-----

Back to work, I guess. I have ideas and half-scribbled notes for several articles that all four readers of this particular parish may be interested in, but even though I now have (more) time - being in sub-saharan Africa, without a direct phone line - the block has so far struck hard. However, the above inspiration has maybe loosened a few cogs, even if only for a little while...

I would show some examples to illustrate this, but then you might lose the impression that I'm a literary genius, and we can't have that.

In my mild angst (you can only be so angst-y when the daily temperature is thirty degrees warmer than your body is used to) I have sought relief at a oft-visited source - the delightful blog Letters of Note, which daily publishes a piece of correspondance that is... well, noteworthy. A recent highlight which I tweeted a few days back was this wondrous reply from the American author E.B. White - he of Charlotte's Web and The Elements of Style fame - on behalf of his dog to the ASPCA. Joyful stuff.

Anyway, I discovered yesterday that the curator, Shaun Usher, recently also opened Lists of Note, which is exactly what it sounds like. And recently, there have been two posts on the subject of writing - both of which I'm quoting below, with no credit taken at all.

First was the great Henry Miller's 11 Commandments:

Work on one thing at a time until finished.

Start no more new books, add no more new material to "Black Spring."

Don't be nervous. Work calmly, joyously, recklessly on whatever is in hand.

Work according to Program and not according to mood. Stop at the appointed time!

When you can't create you can work.

Cement a little every day, rather than add new fertilizers.

Keep human! See people, go places, drink if you feel like it.

Don't be a draught-horse! Work with pleasure only.

Discard the Program when you feel like it—but go back to it next day. Concentrate. Narrow down. Exclude.

Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing.

Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.

This morning, whilst relocating the Miller post, I noticed that today's post is also about writing. Manhattan advertising overlord David Ogilvy sent a memo in 1982 to his employees:

The better you write, the higher you go in Ogilvy & Mather. People who think well, write well.

Woolly minded people write woolly memos, woolly letters and woolly speeches.

Good writing is not a natural gift. You have to learn to write well. Here are 10 hints:

1. Read the Roman-Raphaelson book on writing*. Read it three times.

2. Write the way you talk. Naturally.

3. Use short words, short sentences and short paragraphs.

4. Never use jargon words like reconceptualize, demassification, attitudinally, judgmentally. They are hallmarks of a pretentious ass.

5. Never write more than two pages on any subject.

6. Check your quotations.

7. Never send a letter or a memo on the day you write it. Read it aloud the next morning—and then edit it.

8. If it is something important, get a colleague to improve it.

9. Before you send your letter or your memo, make sure it is crystal clear what you want the recipient to do.

10. If you want ACTION, don't write. Go and tell the guy what you want.

David

*Writing That Works, by Kenneth Roman and Joel Raphaelson

-----

Back to work, I guess. I have ideas and half-scribbled notes for several articles that all four readers of this particular parish may be interested in, but even though I now have (more) time - being in sub-saharan Africa, without a direct phone line - the block has so far struck hard. However, the above inspiration has maybe loosened a few cogs, even if only for a little while...

Monday, 16 January 2012

embarrassing aunt?

Dad remarked the other day that he could tell how busy we - Mrs H and myself - were in preparing to leave the country (on Wednesday coming) by the fact that he'd never known me to be online less, as evidenced by Facebook, Twitter and this blog amongst others. And it's apparently true, as nearly two months have lapsed!

But yes, we're leaving for Niger on Wednesday (18th January.) We've a blog specifically for that on Wordpress.

Anyway, it was my longsuffering Auntie Jane's 50th birthday party on Saturday, and here's an embarrassing video of her as a child. (Apart from the clip 2/3 of the way through in a pram, which is, in fact, my father. But he picked out the clips!)

But yes, we're leaving for Niger on Wednesday (18th January.) We've a blog specifically for that on Wordpress.

Anyway, it was my longsuffering Auntie Jane's 50th birthday party on Saturday, and here's an embarrassing video of her as a child. (Apart from the clip 2/3 of the way through in a pram, which is, in fact, my father. But he picked out the clips!)

Labels:

desert hueys,

huey family,

jane huey,

youtube

Wednesday, 16 November 2011

feverish

In preparation for heading away next year, Mrs H and I have both been going through the classic routine of getting all the rights vaccinations up to date. Mrs H got her few outstanding ones in one go; I, on the other hand (a) needed twice as many, and (b) am a big wuss around needles, and so have spaced mine out much more.

Anyway, was back at the GP on Monday for the penultimate round: in this case, a second dose of rabies in the right arm, and a diptheria, tetanus and pertussis jab in the left. Having never had much of a reaction to any jabs before, I was fairly surprised to come down with a heavy dose of something viral that evening. Cue sleepless nights, blown capillaries (a side effect of violently talking into the Great White Telephone throughout a sleepless night...) colossal aches, and sweating for Ireland. This was all a bit of a new experience, and so is pretty intriguing. Apart from the bit where I managed to vertically faceplant a wall yesterday - that was just weird.

48 hours on, it's mostly passed, bar the headaches (and the sweating - in what is at best a fairly cold office, and am down to T-shirt and still feel roasted) but I still find it weird not quite being able to process what people are saying to me...

Anyway, was back at the GP on Monday for the penultimate round: in this case, a second dose of rabies in the right arm, and a diptheria, tetanus and pertussis jab in the left. Having never had much of a reaction to any jabs before, I was fairly surprised to come down with a heavy dose of something viral that evening. Cue sleepless nights, blown capillaries (a side effect of violently talking into the Great White Telephone throughout a sleepless night...) colossal aches, and sweating for Ireland. This was all a bit of a new experience, and so is pretty intriguing. Apart from the bit where I managed to vertically faceplant a wall yesterday - that was just weird.

48 hours on, it's mostly passed, bar the headaches (and the sweating - in what is at best a fairly cold office, and am down to T-shirt and still feel roasted) but I still find it weird not quite being able to process what people are saying to me...

Thursday, 3 November 2011

get a grip

Just a quick plug/review of a short book I recently picked up - Get A Grip, published by the ongoing BibleFresh initiative, as a spin-off of a current speaking tour they have travelling Great Britain.

Just a quick plug/review of a short book I recently picked up - Get A Grip, published by the ongoing BibleFresh initiative, as a spin-off of a current speaking tour they have travelling Great Britain.The book collects 17 short articles (500 words or so) from a few notable names in UK evangelicalism, which tackle passages of Christian scripture divided in to two categories: lesser-known ones which may give valuable insight, and all too well-known ones which tackle subjects we might wish weren't in scripture at all. I must admit it was the latter of these which drew me in.

I greatly 'enjoyed' the challenge of tackling genocide in Sunday school whilst still there at the start of the year, and will admit I probably learnt a lot more in preparing that session than the kids probably got from me burbling my way through it. I find an awful lot of good can be found in trying to meet these theological brain-melters head on, and I was intrigued to see how far respected thinkers might go on such matters.

Before purchasing, I asked Krish Kandiah whether he thought the short essays were able to tackle subjects like genocide and corporal punishment. 'Pithy but chunky,' came the reply. It might sound more like a good soup, but I reckon that's actually a pretty good assessment.

They're by no way exhaustive - a few of them come across as they only can, as introductions to a topic. But for the price of a cup of coffee, there's a great range of conversation starters. Plus, the whole thing is built around Bible translation and so £1 from every purchase goes straight to funding work in Burkina Faso.

If you're interested, you can pick up a copy direct from the website. Anyone else come across it yet?

Tuesday, 25 October 2011

the crudest equations of faith

Followed a Facebook link down (or up? I can never decide) the garden path to this article by Tim Stanley for the Telegraph, about Richard Dawkins' apparent refusal to debate the theologian William Lane Craig. Whilst it's a pity that Dr Dawkins has declined this particular sparring invite, I can't admit to being too bothered in the grand scheme of things. (If you do like a good argument, I believe the twelve rounds Dr Dawkins went through with Alistair McGrath, author of one of the more useful books I've ever owned is well worth a googling.)

Rather, the reason for blogging about it, dear readers, was this rather succinct observation the author makes:

Good point, well made?

Rather, the reason for blogging about it, dear readers, was this rather succinct observation the author makes:

[We might assume] that [Dawkins] doesn’t understand Christian apologetics, which is why he unintentionally misrepresents Craig’s piece. The most frustrating thing about the New Atheism is that it rarely debates theology on theology's own terms. It approaches metaphor and mysticism as if they were statements of fact to be tested in the laboratory. Worse still, it takes the crudest equations of faith (total submission to an angry sky god) and assumes that they apply to all its believers at all times equally.

Good point, well made?

Thursday, 20 October 2011

labels

I've a long-running, occasionally dipped-in-to discussion with the man-myth-legend Bob about the definitions of things. In life, we don't like labels. I think a major reason for this is because the moment we find one that seems to fit us, we invariably then find ten other people, none of whom we would ever want to have anything to do with, who seem to be appropriating the same label.

Perhaps I'm being harsh here, but then when we have this discussion, it's usually against the backdrop of theological nomenclature. That is, the labels placed on us as members of the worldwide body that comes in the wake of God's ongoing intervention into humanity's history. Reformer, catholic, non-subscribing, presbyterian, anglican, baptist, anabaptist, calvinist, arminian, pentecostal. The list goes on. All of us who belong to the Church in some way or another assume a label, even it's hermit, agnostic, or survivor. It could be argued that none of these are permanent for us; in our meandering journey of discovery, our figurative walk with God, be that left, right, towards or away from, we exist in a constant state of flux between these labels.

I find one I struggle with the most to be 'evangelical'. Hit up Wikipedia and you'll get the four 'key commitments' of the Evangelical movement, born in the British Isles in the mid 18th century:

- 'The need for a personal conversion to the Christian faith';

- A high regard/respect for the authority of the Bible (note that this does not necessarily equivocate to infallibility, but more the notion of biblical inerrancy)

- 'An emphasis on teachings that proclaim the saving death and resurrection of' Jesus Christ, recognised as the Son of God;

- 'Actively expressing and sharing the gospel'

If you're not a God-botherer, then you might well say that sounds broadly like all Christianity. It actually doesn't, but that's a statement for better thinkers than I to tear apart.

But there's a problem. I would strongly identify with those statements. Does that make me an evangelical? It sounds tempting. But you know all those right-wing types in America? Well, they're evangelicals too. They voted for Sarah Palin. I know. Know those churches that seem to exist in a parallel universe from the neighbourhood they're in? They say they're evangelical. The church I grew up in would claim some evangelical types, and there's freemasons on the vestry. Evangelical - really? You still want to be one of those, part of a body that includes Tea Party activists and closet believers and cultish types, churches which spend £30,000 on a new porch when there are kids destroying themselves nearby for the want of someone to actually give them some guidance in life?

But there's a problem with that too, because of course, that's not what the word means. More, like everything it life, it's what we as the people who embody it have become. In many ways, I desperately want to admit to calling myself an evangelical, but the baggage that comes with that (much like calling yourself a Christian) that stymies the words before the make it out of my mouth.

This morning (with a h/t to the Rend Collective's twitter feed) I came across Greg Fromholz attempting to deal with this discussion. It's great to have creative, left-brain thinkers like Greg attempting to deal with this stuff in a way that we normal folk can engage with, so I've shamelessly republished it here. But I'll throw in a heavy plug for his digital book, Liberate Eden which will mess with your head in amazing ways.

--

Friday, 7 October 2011

deserting

In January, the good Mrs H and I are hoping to head to Niger, West Africa with the mission agency SIM. Which is all very exciting, if also terrifying in equal abundance.

In January, the good Mrs H and I are hoping to head to Niger, West Africa with the mission agency SIM. Which is all very exciting, if also terrifying in equal abundance.Nonetheless, as I'm going to be working for SIM Niger as a communications coordinator (whilst my dear wife is busy with, y'know, saving people's lives and all that) it would seem to be fairly conceivable that such things should, of course, be documented on a personal level for all and any interested parties to be able to follow our progress.

However, we deemed that as people who would wish to read about that thing may not necessarily also wish to have their minds populated with movie trailers, rants, getting @gmsythftw elected, video production commentary, theological rants and journal publishing (their loss) we've set up a new blog elsewhere.

Desert Hueys - I know, I KNOW, but YOU try and come up with something better - will document our time up to and whilst we are away in Niger. I hereby promise it will be fascinating, if you like that sort of thing.

Over the next couple of months we're going to try and get as much information out as possible, but DH (as I already affectionately think of it as) may be the primary source for up-to-date knowledge. There's also info about signing up for the more "official" updates, and no doubt this humble blog will remain an outlet for all other stuff that

Thanks to those in the offline world who have already been so supportive, and hopefully online folks may also find their interest piqued by some of the unique and challenging prospects that Niger holds.

Monday, 26 September 2011

the brothers bloom

Having watched it a couple of weeks ago and being bowled over by its unexpected brilliance, I had been meaning to write a short post to point interested travellers towards the 2008 film The Brothers Bloom. I sodding loved it, as did my good wife - a rare bit of concurrence in itself, and testament to the work in question, if nothing else.

However, on a trip to YouTube to find a trailer to embed - well, it became a reminder that more often than not, the guys who cut trailers can be really, really annoying. Somehow, the committee that came up with this one took something that was more up the Wes Anderson line of aesthetics, and turned it in to Ocean's 13.

I can't really emphasise enough how different the pacing of the actual film is. The narrative clips along at a right old pace - it is a con caper, after all - but the extra beats inserted, particularly after gags (which often just occur without any build-up) are completely absent from this trail. And all the other trails I found in my short browse.

It's pretty much an advertisement for a completely different film, to my mind. I wonder if anyone else seen both and can offer a reaction...